Thinking about the media, colonialization, nation-building discourses and their impact on the reconstruction of the precolonial past in Southern Central America.

The Gulf of …what?

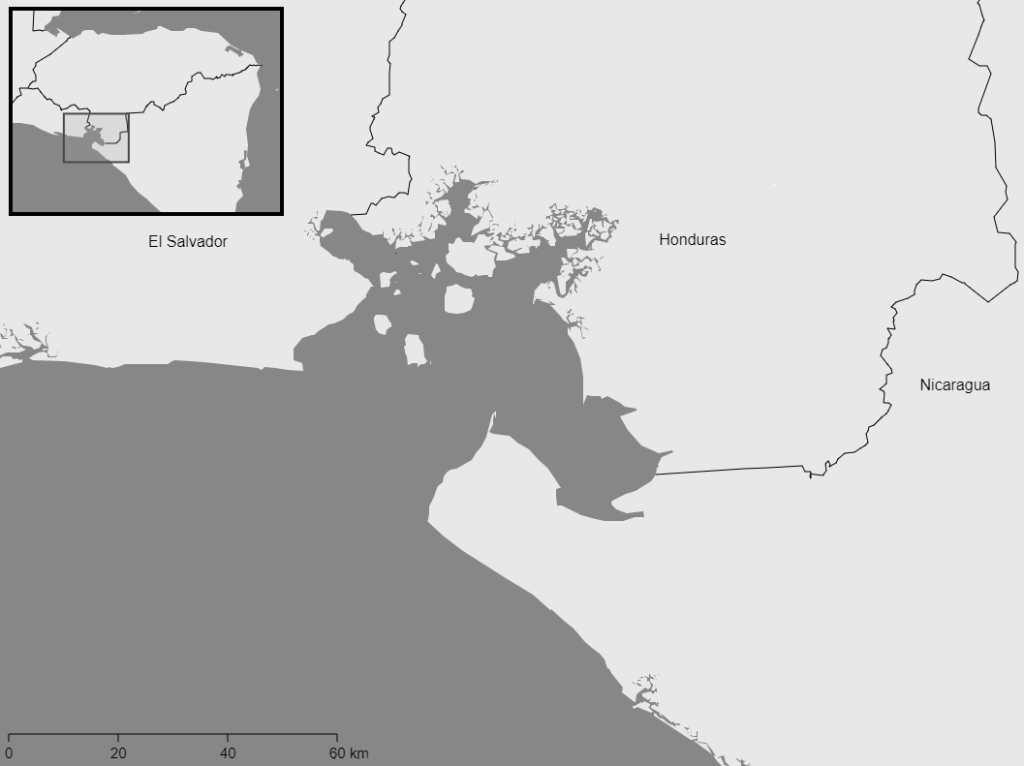

Fair enough. It is not the biggest of Gulfs, and if you have never been to this neck of the woods, or if you research doesn’t have you poking around Central America, it’s certainly legitimate if the name doesn’t ring a bell. Still, as far as Central American (pre)history is concerned, it is a pretty significant place. Located on the Pacific Coast, and divided between the modern nations of El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua, the Gulf of Fonseca has been a point of contention for most of its history.

The diverse environments of the Gulf certainly made it a prime location to settle for past dwellers, with the numerous rivers flowing into the Gulf of Fonseca offering travelling opportunities inland and along the Pacific Coast. However, as much as we can hypothesize, we know relatively little about the region’s precolonial settlers compared to other areas in Central America. But where is this poor understanding of the Gulf of Fonseca rooted? Certainly not in the lack of precolonial occupation, as recent research is starting to show (Brown and Vasquez 2014, Gomez 2010, Kolbenstetter 2021, Valdivieso 2006).

Reading into the historiographical void

Part of the answer lies, I would argue, in the early colonialization of Pacific Central America. The first European landing in the Gulf of Fonseca is attributed to Andres Niño, in 1522. However, Niño probably didn’t step off the ship, and his description of the Gulf remained superficial at best. Only a century later does the first elaborate description of the Gulf enter in the books. Fray Alonso Ponce, a Franciscan chronicler, describes a fairly low density of indigenous settlements in the Honduras and Nicaraguan parts of the Gulf, as well as only two inhabited islands in the Gulf (Ponce 1873 [1583]. And while this was written over 150 years after Niño’s first account (never mind that records indicate that 90% of the indigenous population was eradicated within 30 years of conquest), this account somehow sparked the idea this area was barely populated in precolonial times. This idea later persisted for over a century of Central American scholarship, leaving the claim uncontested.

Sitting right between the influence sphere of the governorships of Nicaragua and Guatemala, the territory of the Gulf became a source of conflict from early on. Records hint at the fact that neither governor, seeing the Gulf as the outer periphery of their territory, really bothered for the land. They did, however, care and fight about the potential riches that were to be acquired through the enslaving of the population (Gomez 2010). Before any record of its indigenous inhabitants appeared, the area was sacked and its inhabitants reduced to slavery. Since then, boundaries have stood in the way of building a precolonial narrative for the Gulf of Fonseca.

Nation-building and archaeology

In the 1800s, stuck with flimsy borders inherited from imperial Europe, the newly independent states of El Salvador, Honduras and Nicaragua set out their national agendas. Nation-building discourses promoting these agendas soon resulted in territorial conflicts (Benitez Lopez 2018) . Already divided since colonial times and becoming a renewed geostrategic interest, the Gulf landed in the middle of this dispute. Foreign powers interested in the development of a trans-oceanic railway project and in a port on the Pacific certainly played a big part in fueling and maintaining the dispute (Rivas 1934, Squier 1878). Although, legally, the territorial conflict was resolved in 1992 by the International Court of Justice, tensions continued well into the 2000s

The ghost of these nation-building discourses is still to be seen in the fragmentation of the archaeological narrative. The few existing archaeological studies relate the finds from the West coast of the Gulf to a Salvadoran tradition, finds from the northern side of the Gulf to a Honduran tradition, while archaeologists of Pacific Nicaragua have mostly assumed that the archaeological Greater Nicoyan tradition incorporated the Nicaraguan part of the Gulf of Fonseca, diligently stopping at the border.

Central American archaeology and the media

But nation building discourses and boundaries are not the only ones that have maintained the myth of emptiness in the Gulf of Fonseca. The western media also holds a fair share of responsibility when it comes to misrepresentation of Central America’s past. By now, the idea that monumental archaeology is the only thing sexy enough to promote is well anchored in Central American archaeology. But archaeological scholarship has long fallen victim to this trend as well, leaving the archaeology Gulf of Fonseca and many other regions in Central America in the shadows of the Maya. The issue with this phenomenon is that it has not only resulted in visibility issues on an international level, but also on a local level. With its strategies, the media has shaped what heritage should be considered of value, leading many communities to believe that there is no value in the archaeology surrounding them.

The need for a local narrative in the global present

The Gulf of Fonseca’s contradictory status throughout history, as a contested periphery has left its population one of the poorest in Latin America. Many of its inhabitants rely on a subsistence economy based mostly on traditional lifeways dependent on the environment. The traditional subsistence practices of fishing and mollusk collecting are progressively threatened by climate change, aquaculture and commercial overfishing. The planned development of large port facilities on the coast of El Salvador and on the island of El Tigre in Honduras, while perhaps boosting the regional economy, will come at the expense of the crumbling ecosystem. Creating a trinational narrative of the Gulf’s precolonial past then holds the potential of raising much needed awareness to the value of landscapes in which people have been living, hidden from global records, for over two thousand years.

Feature Image: Map of the “Gulf of Amapall”, William Hack, 1685.

This blog was originally published under the same name on the Scottish Centre for Global History Blog in July 2021.

Bibliography

Brown, C. and R. G. Vasquez, 2014. Reconocimiento, Prospecciones y Excavaciones en el Departamento de Chinandega, Nicaragua, Temporada 2, Informe Final. Report presented to the Instituto Nicaragüense de Cultura, Managua.

Gomez, E., 2010. The Archaeology of Colonial Period Gulf of Fonseca, Eastern El Salvador. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of California Berkeley.

Kolbenstetter, M.M. (forthcoming). The Gulf of Fonseca, Archaeology of. In Claire Smith, (ed.) Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. Springer: New York

Valdivieso, F. (ed). 2006. El Golfo de Fonseca: Colección de estudios culturales. San Salvador: Casa de las Academias.

Ponce, A., 1873 [1583]. Relación breve y verdadera de algunas cosas que sucedieron al padre fray Alonso Ponce en las provincias de Nueva España. 2 vols. Madrid: Imprenta de la Viuda de Calero.

Gomez, E., 2010. The Archaeology of Colonial Period Gulf of Fonseca, Eastern El Salvador. Unpublished PhD dissertation, University of California Berkeley.

Benitez Lopez, J., 2018. El Golfo de Fonseca como punto geoestratégico en Centroamerica. Mexico: Bonilla Artigas Editores

Rivas, P., 1934. Monografía geográfica e histórica de la isla El Tigre y puerto de Amapala. Tegucigalpa: Talleres Tipógraficos Nacionales.

Squier, E., 1878. The States of Central America. New York.